Potlatch Ceremonies & The First Nations of North Vancouver Island

Date:

Author:

The northern region of Vancouver Island in British Columbia (BC), with its abundant wildlife, dense forests, and unique geographical features, is truly a retreat to the rugged wilderness. Travellers to this area enjoy a chance to connect with nature while also learning about the history of the land and the Indigenous groups that are native to the region.

The original inhabitants on Northern Vancouver Island were the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw (pronounced: KWOK-wok-ya-wokw) First Nations, an indigenous group of people who speak the Kwak̓wala language. Within the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw are several distinct tribes, including the Kwagu’ł of Fort Rupert and the ‘Na̱mǥis in Alert Bay.

The Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw are widely regarded for their artwork, with their bold colours and symbols reflective of BC’s coastal Indigenous culture, along with their traditional dances and ceremonies such at the Potlatch. While travelling on the North Island we hear a lot about potlatches, so let’s dive into what this tradition means for the First Nations in BC, and specifically the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw.

The Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw Territory

The traditional Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw territory spans the north eastern region of Vancouver Island and mainland British Columbia, from the northern end of the Strait of Georgia to Cape Cook, Queen Charlotte Strait and the inlets leading into it. Pre-European contact, the estimated Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw population was over 19,000, however by 1924, this number had fallen to just over 1,000. As such, the preservation of the culture and history of the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw, and of all First Nations in Canada, is vital.

What is a Potlatch Ceremony?

Potlatch ceremonies are a traditional gathering held by many First Nations groups in the interior western subarctic and on the Northwestern coast of Canada and the United States. For the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw people, the potlatch is used to mark every event of significance and to keep their history alive through the witnessing and oral retelling of cultural and spiritual practices. These vibrant ceremonies are a time of giving, pride, dancing, and showing of the masks.

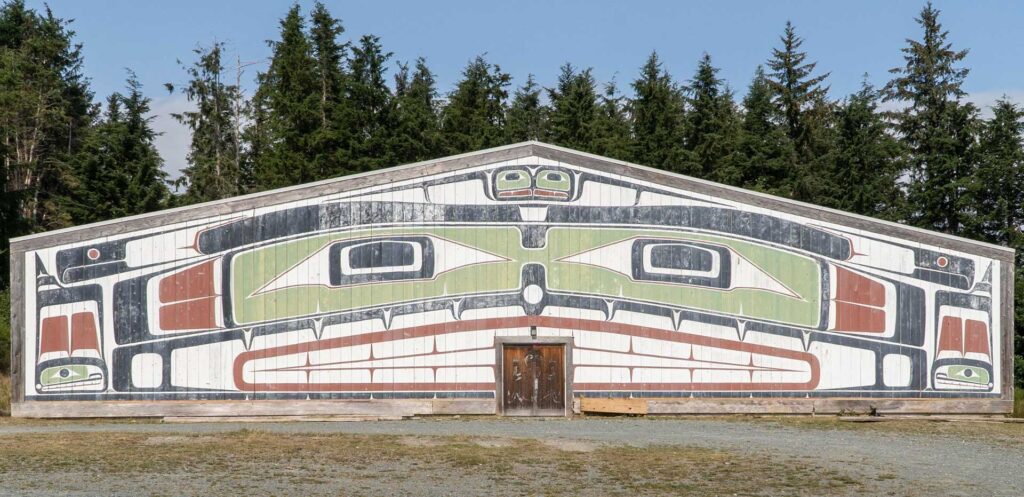

Ceremonies would be held in the Big House, or Gukwdzi, by the Chief and would often last up to several weeks during the winter months. In the past and still today, Big Houses serve as a cultural and spiritual gathering place for the First Nations. They are the centre of governance and many traditional practices. Their size was often indicative of the status of the host, the Chief, in the village. Larger Big Houses would have the capacity to bring together hundreds of guests from various First Nations across the region.

Potlatch Gifts

The word ‘potlatch’ means ‘to give’, and comes from Chinook trade jargon formerly used along the Pacific Coast of Canada. Potlatches once served as the primary economic system of the coastal First Nations, as these gift giving ceremonies were a way to redistribute wealth between families.

Goods such as clothing and copper were exchanged, along with larger gifts including land, family rights and inheritances.

While this type of economic system is no longer prevalent in society today, gift giving remains at the heart of the tradition.

The gifts that are given during the potlatch ceremony have evolved over the years. In the 19th century, gifts included animal fur and hides, blankets, carved cedar boxes, and canoes. Gifts in the 20th century included carvings, copper bracelets, sugar and flour, and with the expansion of the Hudson’s Bay Company to BC, Hudson’s Bay blankets.

One gift that has stayed consistent over the years is eulachon oil, extracted from the eulachon fish or t̕łi’na in Kwak̓wala. Eulachon oil has many uses including cooking oil and traditional medicine, and remains one of the most valuable potlatch gifts as well as a feast delicacy.

The Potlatch Ban

Under the Indian Act in Canada, potlatch ceremonies were banned by the Canadian government between 1885 and 1951. The ban was part of a larger effort by the government to assimilate Indigenous culture, traditions, and values to match a European framework. As a result, First Nations community members were persecuted for participating in cultural practices, many of their Big Houses were torn down, and ceremonial objects and masks were burned and confiscated.

In 1921, after the ban had been in place for over three decades, Dan Cranmer of the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw held the largest recorded potlatch ceremony in BC’s northwest coast. The Cranmer family, recognizing the need to preserve their songs and traditions, had been keeping the potlatch alive for generations. Despite it being outlawed, Dan Cranmer held this potlatch with at least 300 guests in secret at the village of ʼMimkwa̱mlis, a remote island east of Alert Bay.

The Cranmer’s potlatch ceremony was discovered by federal authorities and raided, which led to the arrest of 45 individuals. Those arrested were given the choice between surrendering their potlatch regalia to suppress future ceremonies, or going to jail. Around half of the people who were arrested chose to go to jail, while over 750 items were confiscated.

In 1951, the Indian Act was amended and the potlatch ban was lifted, however it still took several years for some communities to feel comfortable hosting a potlatch again. The first potlatch in BC after the repeal was held in 1953 by Chief Mungo Martin in Victoria.

The Revival of Potlatch Ceremonies & Collections

Potlatch ceremonies remain as important a tradition as they were centuries ago. Abundant with songs, food, and dancing, much of what made the potlatch such a vibrant cultural practice is still present today. A key distinction to potlatches of the past is that historically, gifts were given according to the social status of the guests, however in present day, gifts are given to all invited guests. Potlatch guests are considered witnesses who acknowledge what has been passed down in the ceremony and they are thanked through the offering of gifts.

Now over 40 years since the Cranmer Potlatch took place, the items that were confiscated from the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw have been slowly repatriated from museums and private collections around the world through efforts of dedicated community members and the Federal Government.

In 1979 and 1980, the U’Mista Cultural Centre in Alert Bay and the Nuyumbalees Cultural Centre in Cape Mudge were established to house the repatriated items. The Federal Government required the cultural centres be built so that the items could be returned from museums and collections back to their rightful communities while ensuring that they remain protected. Some items are still in the process of being repatriated today.

Sharing of Culture with Visitors

Community connection, storytelling, and engaging performances bring this history to life during our tours to North Vancouver Island. Travellers can learn more about the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw and the history of the potlatch by visiting the impressive collection of masks and regalia housed at the U’Mista Cultural Centre in Alert Bay. You can also learn about the Potlatch Collection virtually.

In July and August each year, we join the T’sasala Cultural Group in the ‘Na̱mǥis Big House for a dance performance where many of their traditional masks and regalia are used. T’sasala is an impressive community group comprised of over 80 members dedicated to teaching the children and youth in the community about their ancient dances, beliefs, and values, while educating the world through performance.

Ready to join us on a journey of adventure, culture, and wildlife? Visit our website to learn more about our guided and self-guided tours on northern Vancouver Island.